If this is the first you're hearing of Laowa (sometimes known as Venus Optics), I'm sure it won't be the last. They are a relatively new Chinese lens manufacturer, and they have been making some really cool and unique specialty lenses. First, they came out with the 60mm 2:1 Ultra Macro lens, you can read my review here. Next came their 15mm Wide Angle Macro, which was the first one I purchased, you can read that review here.

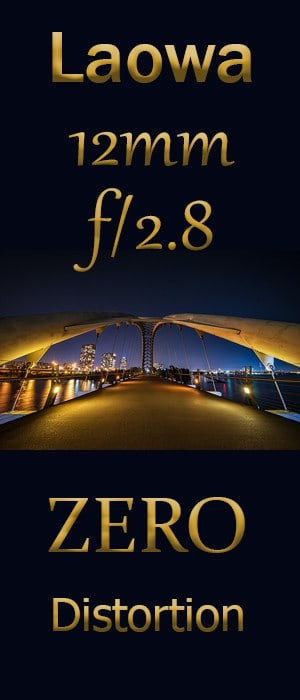

Now, they have been kind enough to loan me one of their most recent offerings so that I could take it for a test drive. I'll admit that I hate to give it back. The Laowa 12mm Wide-Angle Zero D has a lot to get excited about, claiming a super wide angle of view with a fast aperture (hello, astrophotographers), and amazingly little distortion (although “zero” may be a slight exaggeration). I think this lens could earn a place in many a landscape, astro, real estate, or architectural photographers' bags.

The Tech Specs

The Laowa 12mm f/2.8 Wide-Angle Zero D lens is, as the name implies, a 12mm prime lens with a fast, f/2.8 aperture. That gives you a 122-degree field of view, making it the fastest rectilinear (non-fisheye) lens currently available at such a wide angle. This lens is 12mm on a full frame camera, which is fairly remarkable, and claims zero distortion, meaning that lines, even near the edges stay straight. Wow.

It is available in the following mounts:

- Nikon

- Canon

- Sony A and E

- Pentax

The lens will set you back around $949 USD, whether you purchase it from Amazon (who seem to only have Sony and Pentax mounts available), or directly from Laowa. A little pricey for a manual focus lens, but it is, for now, the only one of its kind. If you choose to add on the 100 mm filter holder, that will be an extra $70 -75 USD. Since landscape photographers love their circular polarizers and neutral density filters, I'm sure they'll sell more than a few of those holders!

Distortion

So, what does the Zero D claim mean? A wide-angle lens traditionally creates distortion, and the wider the lens, the more distorted the image. One way that a wide-angle lens causes distortion is that anything close to the lens appears much larger than objects that are further away, even if they are in fact much smaller. For example, we've all seen photos with a wildflower in the foreground that looks huge compared to the mountain in the background. The wide-angle lens exaggerates this perspective much more than our eyes do. The Laowa 12mm Zero D lens does not correct this type of distortion. What it does eliminate, almost completely, is barrel distortion. Barrel distortion is where the lines in an image bulge outwards at the center, especially around the edges. If you think of the distortion in a fisheye image, it is a lesser version of that rounded effect. This won't be a big issue for landscape photographers. There are few perfectly straight vertical lines in nature unless maybe you're at a tree farm. It is a huge issue for architectural and real estate photographers, though. Rows of columns, walls, and windows make barrel distortion very obvious.

What it does eliminate, almost completely, is barrel distortion. Barrel distortion is where the lines in an image bulge outwards at the center, especially around the edges. If you think of the distortion in a fisheye image, it is a lesser version of that rounded effect. This won't be a big issue for landscape photographers. There are few perfectly straight vertical lines in nature unless maybe you're at a tree farm. It is a huge issue for architectural and real estate photographers, though. Rows of columns, walls, and windows make barrel distortion very obvious.

In the comparison photos above, notice the barrel distortion occurring in the left-hand image (red arrow), compared to the straight lines in the photo on the right. These were taken using a tripod, in the exact same place and position, on a full frame camera, changing only the lens. It is amazing the difference the extra 3 mm makes on the wide-angle end. (A 3mm difference on a telephoto lens would be barely discernable). While the Laowa 12mm Zero D did an admirable job of keeping lines straight, the crazy distortion of the light fixture is the price you pay.

Real Estate Photography

The extreme wide-angle view of this lens makes it a bit of a cheat for real estate photography, especially on a full frame camera. That being said, it is AWESOME for maximizing a small space…perhaps to the point of dishonesty. It would also be an excellent and affordable wide angle lens for photographers using a crop sensor camera, as it will give you an equivalent focal length of around 18mm.

The photo above shows the difference, this time comparing the Laowa 12mm with a Nikon 20mm lens. My tripod is standing right at the bottom of the staircase. As you can see in the previous set of photos, there is only about 2 feet of space to fit in there. Both lenses create very sharp, appealing “light stars” when stopped down to f/16, as they were in these examples.

Manual Focus – Why It Doesn't Matter

The Laowa 12mm Zero D is a manual focus lens, but if there was ever a time to not get super hung up on the lack of autofocus, it's with an ultra-wide lens like this one. The wider the focal length, the deeper your depth of field and the closer to the front of the lens your hyperfocal distance will be. The hyperfocal distance is the closest point at which you can set your focus and have everything from that point forward in the scene be “acceptably” sharp. Honestly, I've found with this lens that you can play pretty fast and loose with your focusing and it is hard to go too far wrong. In fact, when I enter the 12mm focal length into this Depth Of Field Calculator, it says the hyperfocal distance is at only 1.02 feet in front of the lens. You've got a lot of room for error.

Another reason that the manual focus is a non-issue is that so many of the common applications for the lens require the use of a tripod. This gives you plenty of opportunities to zoom in on live view and perfect your focus. The one night shoot I did with this lens, I focused a few feet in front of me and never even touched the focus again, although I moved around plenty. The photos are all very sharp.

Manual Aperture…This Matters A Bit More

The manual aperture means that you change f/stops using a ring on the lens, rather than a dial on your camera. It means that the camera does not know what aperture you're using, although most will still be able to meter the light and allow you to use the Aperture Priority mode. Strangely, my Nikon D750 kept guessing at the aperture being used (incorrectly), which I've never seen it do with any of my other manual aperture lenses. Thankfully, it didn't save its speculations to the metadata in the photos.

Using the manual aperture dial is not a big deal. The main drawback to manual apertures is that the view through your viewfinder becomes darker as you stop down. When the camera controls your aperture, it leaves it wide open while you focus and only snaps it shut when you release the shutter. The manual dial means that you are closing the aperture down when you set it, allowing less light through to focus with. The solution with most modern DSLR's is to use live view, which shows you the light hitting the sensor. At least during daylight hours, this will be quite sufficient. At night, it is a whole other story, and in writing this, I just realized where I went wrong in taking the photo below:

Because the arch of the bridge was not lit, I was unable to see it at all at f/16, even using live view. As a result, I had to guess at my centering, use the bubble level, and rely on trial and error and luck. The photo above, which has not been cropped or had distortion corrected in any way (because I wanted to show the exact field of view for this article), is slightly askew and it's making me crazy. I fixed it up a bit for posting in other places online (you can see my final, more symmetrical edit here if you're interested). The epiphany I just had was the realization that all I needed to do was to open the aperture to f/2.8 while I composed my scene and then stop down to f/16 to take the photo. Doh. Live and learn. Maybe I'll sneak back out there one more time before I return the lens 😉

Astrophotography

The Laowa 12mm f/2.8 Zero D is a dream lens for astrophotographers. Although weather conditions and timing were not in my favor to test it out myself, it all adds up on paper. For pinpoint stars and a sharp, detailed milky way, the wider the angle, the longer the exposure time you can get away with. At a 12mm focal length, on a full frame camera, you could expose the night sky for around 42 seconds before the earth's rotation would start to blur those points into trails. (Based on calculations from the handy Photo Pills app). Wide open, at f/2.8 that should result in a very bright Milky Way! On the other hand, if star trails are your goal, the 122 degrees of view gives you a whole lotta sky to play with. There are some amazing photos on the Laowa website, here and on their gallery page here (just pick the lens from the drop-down menu).

Some of the other reviews I have found online do report some batwing coma distortion of the stars near the edges. Coma distortion is when the stars take on a smeared, stretched, oval appearance. The batwing coma effect gives them a stretched out cross appearance, almost like a bird (or bat) in flight. This is a pretty common issue in astrophotography. All wide angle lenses have these problems to some degree, but there are some that are reported to handle it better. (Rokinon, is one example that many astrophotographers seem pleased with, though I have not tried their lenses, myself). Luckily, this issue is only really visible when zoomed in to 100%. Unfortunately, there is little that can be done to correct it in post-processing.

Sun Stars

Not all wide angle lenses create a pleasing, sharp, well-defined sun star effect when stopped down and pointed at a light source. For example, my Nikon 16-35mm lens has ugly light stars and flare. I don't know how else to describe it, it just looks bad. Although the photo to the right is rubbish, it shows a very pleasing sun star and flare. I was quite happy with the effect on the lights in the night photo of the bridge above, as well. Usually, you need to be stopped down around f/16 to really start seeing this effect. Once again, the extreme wide-angle of the Laowa 12mm Zero D is advantageous, in that you'll start to see lights turning into pointed stars as soon as around f/5.6.

Conclusion

So, will I be purchasing the Laowa 12mm f/2.8 Wide-Angle Zero D lens? Not at this time, BUT only because I invested in the Nikon 20mm f/1.8 earlier this summer. If I did not have a fast, wide-angle prime, this would be a real contender. It is really sharp, really wide and the distortion control is amazing. I wouldn't be a bit surprised if I found a way to justify adding it to my bag at some point!

Love the way you explain things. Well written. Thank you

Thanks, Matt! I’m glad it was easy to understand.

For Nikon, you can enter the lens data as a non-CPU lens. In this way, can still have matrix metering.