From the sunset picture example, you have learned the importance of taking full control over the exposure on your camera. Now, it's time to dig into your camera and learn the three most basic tools available to you in controlling the exposure.

Those tools are shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. After I explain what each one does, I'll explain why we need three separate tools to control the brightness or darkness of the photo.

Aperture

The aperture is a small set of blades in the lens that controls how much light will enter the camera. The blades create a octagonal shape that can be widened (we photogs call it shooting “wide open”), or closed down to a small hole. Obviously, if you shoot with the aperture wide open, then more light is allowed into the camera than if the aperture is closed down to only allow a tiny hole of light to enter the camera.

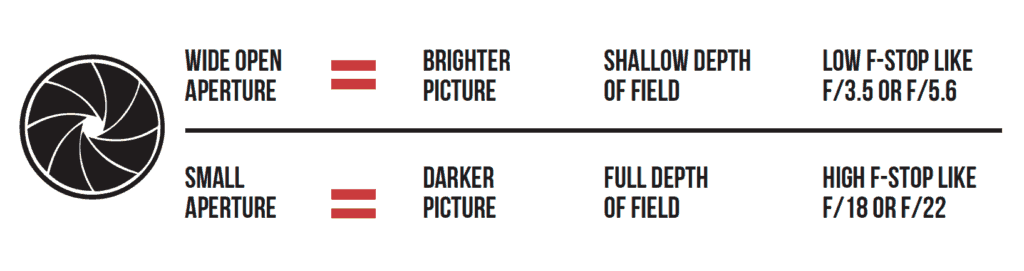

So suppose you take a picture that is too bright. How do you fix it? Simply choose a smaller aperture. Simple! Aperture sizes are measured by f-stops. A high f-stop like f-22 means that the aperture hole is quite small, and a low f-stop like f/3.5 means that the aperture is wide open.

Let's test your knowledge to make sure you have it down. If you take a picture and it's too dark at f/5.6, would you choose a lower f-stop number or a higher one? Yep! You'd choose a lower f-stop number, which opens up the aperture to let in more light. The size of the aperture controls more than the brightness or darkness of the picture, though.

The aperture also controls the depth-of-field. Depth-of-field is how much of the picture is sharp, and how much is blurry. If you want to take a picture of a person with a blurry background, you'd use shallow depth of field. If you want to take a picture of a sweeping mountain vista, you'd want to use a small aperture size (high f-stop number) so that the entire scene is in sharp focus. If you, like me, are more of a visual learner, then I think this graphic will help solidify the information about aperture. Take a minute and make sure you understand this info before moving on.

Shutter Speed

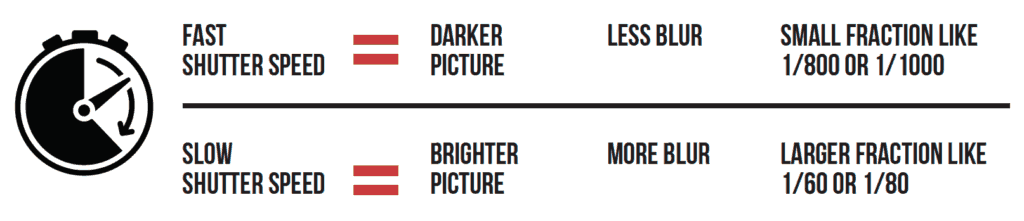

The shutter is a small “curtain” in the camera that quickly rolls over the image sensor (the digital version of film) and allows light to shine onto the imaging sensor for a fraction of a second. The longer the shutter allows light to shine onto the image sensor, the brighter the picture since more light is gathered. A darker picture is produced when the shutter moves very quickly and only allows light to touch the imaging sensor for a tiny fraction of a second. The duration that the shutter allows light onto the image sensor is called the shutter speed, and is measured in fractions of a second. So a shutter speed of 1/2 of a second will allow more light to touch the image sensor and will produce a brighter picture than a shutter speed of 1/200 of a second. So if you're taking a picture and it is too dark, you could use a slower shutter speed to allow the camera to gather more light.

Just as the aperture affects the exposure as well as the depth-of field, the shutter affects more than just the exposure. The shutter speed is also principally responsible for controlling the amount of blur in a picture. If you think about it, it makes sense that the shutter speed controls how much blur is in the picture.

Imagine me sitting here at my computer desk waving to you (you don't have to imagine very hard if you just look at the picture on the right). If you take a picture of me with a shutter speed of 1/30th of a second, then my hand will have moved in the time that the camera is recording the picture. To get rid of the blur, you need to increase the shutter speed to around 1/320th of a second. At this speed, my hand is still moving, but the camera takes the picture so fast that my hand travels only such a small distance that it is not noticeable in the picture.

The next question that most people ask is, how slow of a shutter speed can you use and still get a sharp picture? My blog post on Minimum Shutter Speeds will answer your question!

ISO

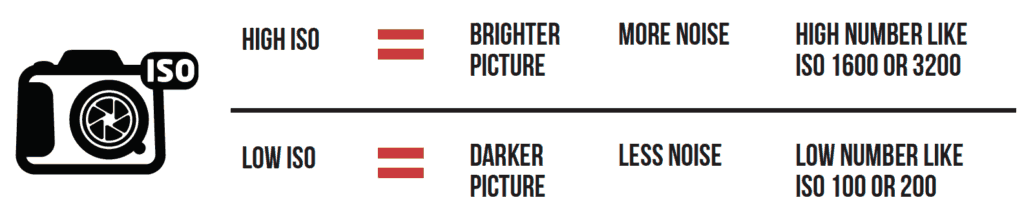

The funny thing about ISO is that it is an acronym, but nobody really knows what it stands for. It is always just called ISO even though it really stands for International Organization for Standardization. Every once in a while, you'll hear an older photographer pronounce it “I-so”, but almost everyone pronounces it “I.S.O.” The ISO controls the exposure by using software in the camera to make it extra sensitive to light.

A high ISO such as ISO 1,600 will produce a brighter picture than a lower ISO such as ISO 100. The drawback to increasing the ISO is that it makes the picture noisier. Digital noise is apparent when a photo looks grainy. Have you ever taken a picture at night with your cell phone or your pocket camera, and noticed that it looks really grainy? That is because the camera tried to compensate for the dark scene by choosing a high ISO, which causes more grain.

What constitutes a “high” ISO is constantly changing. Camera companies are constantly improving the ability of cameras to use high ISOs without as much grain. A few years ago, only the highest-end pro DSLR cameras could achieve 2,000 ISO, and now even entry-level DSLR cameras can shoot at this level. Since each camera is different, you would do well to do a few tests with your camera to see how high of an ISO you can shoot at without making the image overly grainy.

Right now, you will commonly find new DSLRs that advertise expandable ISO ranges.

Putting It All Together

I know exactly what you're thinking. “Why do I need three tools to control the exposure? Wouldn't one suffice?” The answer is no, and I'll explain why with an example. In January, I took a trip to my favorite place on the planet to take pictures–Yellowstone National Park. My guide informed us that the bighorn sheep in the park were dying off very quickly due to whooping cough, so I worked hard that week to capture pictures of the last few sheep in that area of the park.

Around 9AM on a cloudy day, I found a small group of bighorn sheep and started photographing them with a long 600mm lens. The early hour and clouded sky made the situation quite dark for shooting.

Let me help you out. The lens I was working with cost around $12,000, but don’t worry. You can get really good results with a much more affordable 600mm lens. I’m considering selling my expensive lens.

Anyway, it had a maximum aperture size of f/4. So I set my aperture at f/4 to gather as much light as possible. This also impacted the depth-of field to blur out the rocks behind the bighorn sheep. Next, I set my shutter speed. I wanted to capture action in the photo, so I set my camera to 1/1000th of a second shutter speed. I knew that this fast of a shutter speed would prevent any motion blur from the sheep running on the mountain side. Then, I took a picture. WAAAY too dark! I couldn't compromise my shutter speed or aperture, so I knew I needed to use the third player in the exposure triangle–the ISO.

I played around with my ISO and found that if I increased it to ISO 640, it made the picture bright enough to take the picture without making it overly grainy. This combination of shutter speed, aperture, and ISO worked out perfectly. It feels so good to hone in the camera settings!

Now can you see why you need to know how to shutter, aperture, AND ISO, and know how to set them independently on your camera!

If you're a visual learner and want to really learn your camera, then be sure to check out my Photography Start Course. Just a reminder, it's a series of 22 videos where I take you on location to shoot waterfalls, landscapes, people, kids, and macro photos. You can look over my shoulder and see exactly how I set up my camera to take professional photos.

Now, you need to learn how to apply these settings on your camera to take advantage of your new-found nuggets of knowledge.

This was very good and really helped. Thank you so much!

Thanks bro, wonderfully & simply explained.

Indeed a very helpful lesson. Thanks a lot.

Really helpful dude……#goodjoob#bro#lovedit…..!

This has helped me out so much! Thank you!

Detailed to the last

thank you.. it was helpful.

Excellent guide and its what I am looking for.

Thanks!

Amazing help to me!

This is an excellent post, in what looks to be a great series of them Jim. I’ve been messing around with cameras and photography since I was 14 — I’m 63 now. I’d like to think I know a thing or two about cameras and photography in general, BUT as I frequently discover, I don’t know nearly as much as I should . . . or thought I did. I’d never heard of the triad of aperture, shutter speed and ISO before, but it makes perfect sense. And it gives the photographer considerably more control of the image.

I guess I’ve had a difficult time changing from the days of film when you were saddled with one film speed — known way back when as the ASA. The initials ASA stood for the American Standards Association and referred to the way both black and white and color film speed was rated. ASA scales were calculated arithmetically and each film type had their own ASA. For example, the Kodak line of 35mm black and white negative films included: Tri-X with a 400 ASA, Plus-X Pan with a 125 ASA and Panatomic-X had a slow 32 ASA. You used Tri-X for outdoor sports without a flash and indoor sports with a flash and indoor natural light (it’s versatility made it a the go-to film of newspaper photographers); Plus-X was a great all-around film to use on bright, sunny days and with a flash indoors; and Panatomic X was used for portraits and stationary. pictures with a flash or if you wanted to shoot outdoors and capture the blur of movement, like waterfalls. ASA was sometimes used interchangeably with the term “Exposure Index” (EI). But I and most of my friends used EI as a reference of how much a film was “pushed”. Since we were stuck with the film with a specific ASA we had to rely on pushing a film to a higher EI to make it faster and therefore more usable in natural light. The first thing the photographer had to do was to shoot the film at a higher ASA than the film was rated for. The problem was that when a film was pushed, it’s graininess also increased sometimes to the detriment of the quality of the photograph. There were ways to minimize grain, though. For example, it was not uncommon to push Tri-X up to an EI of 800 or even 1600 using a developer like Acufine which helped keep the grain down. Kodak always included recommended developing instructions and times for a variety of developing agents in their packaging. If you developed the film at the temperature and for the time Kodak recommended for a developer like Acufine you might end up with a pretty usable negative at the end of the process. Anyway, now there’s ISO which replaced ASA as a speed rating sometime in the 1980s. And then digital photography came along which made the art form much easier to get started in and master . . . thanks to people like Jim and his blog. Sorry to wander off on such a tangent, but the discussion of ISOs, apertures and shutter speeds just triggered me into a need to reminisce and provide some perspective for persons just learning to use this wonderful tool.

Thanks for such a nice article!

One small correction: it should be f-22 not f/22 in the Aperture diagram.

It really doesn’t matter. Aperture values are written with the slashes much more than with the dash.

Sorry, John. What I should have said was that I think you meant he should have put it as f/22 and NOT as f-22.

Thank you for explaining everything so simply. I was having trouble understanding the correlation of the three by reading other blogs. The way you explained it makes sense. Thank u!

Hi, I have one question regarding aperture. Wide Open Aperture means Full-Depth-Of-Field or Shallow-Depth-Of-Field? This is a bit confusing because in the tutorial link 3, where you have provided an example of capturing the entire family member and whether to choose potrait mode, you said that – “portrait mode on your camera automatically makes the aperture go really low, because it thinks you want shallow depth-of-field in your portrait”.

But in the above explanation , you said , small aperture means Full-Depth-Of-Field. Please explain this.

Wide open means a shallower depth of field, which means less of your picture is in focus; a smaller aperture means a greater, more extensive depth of field, meaning that more of your picture from front to back will be in focus.

Thank you so much 🙂 that is really helpful

Thank you for helping all us noobs out! It’s one thing entirely to point and click with an iPhone but a completely different beast when you want to learn how to shoot photos that can be framed and hung on your living room wall. Just bought my first DSLR (Nikon D3100) and I’m learning just how demanding real photography is! Thanks again for helping me learn!

You have the gift of teaching! Clear, concise and well written!

THANK YOU

Simply superb.

fu

lol sry I meant to say shutter

lol sry i meant to say shutter

The good you are in photography goes same with explaining it. Truly amazing tutorials.