But seriously, let's hope that none of us go there. Please, don't be this guy.

Fly your drone close to manned aircraft

I'm sure licensed pilots love the company of their little sky buddies when they are trying to land or take off. It probably helps combat boredom.

Don't even think of being this person. If there is one scenario that aviation regulators most want to avoid, it is the possibility that an unmanned aircraft system (UAS) will interfere with manned aircraft operations. The potential danger in such interaction is obvious. Sadly, it has not stopped some irresponsible UAS operators.

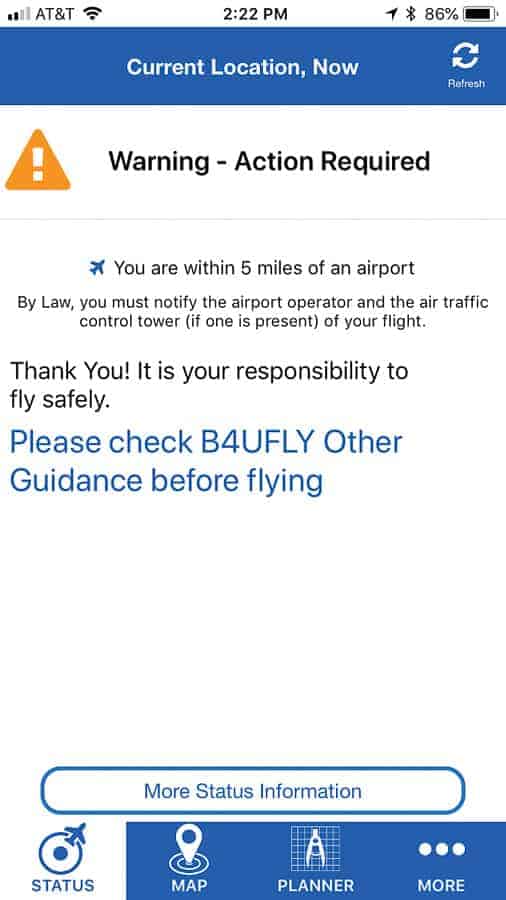

The FAA app entitled “B4U Fly” is a simple and extremely convenient tool for drone pilots. It uses your smartphone's GPS to instantly let you know if you are within 5 miles of an airport. If you've used the app, you were probably as surprised as I was to find out how many airports there are around you. It's not only the commercial travel airports that make the app–but small municipal airports and air strips you might not know were out there–show up in the app.

The B4U Fly app is not only a useful, sensible way to leverage technology. It's also sound policy. Rather than treat every drone pilot like a suspected criminal, or demand a conventional pilot's license from every drone pilot, it seems as though the FAA has chosen a different path. It has made the process of registering a drone and flying it for recreation a painless process. The smartphone app makes drone safety a cooperative endeavor between pilot and regulator.

Fly directly over the heads of people.

Fly directly over the heads of people.

If you really want to make your drone photography hobby or business the kind of friendly neighbor that everyone invites over for the BBQ, then by all means fly it directly over people's heads. And the closer the better! Nothing's more enjoyable than being surprised by a hovering camera that makes an insect-like buzzing sound while being just out of your visual range. You're sure to make everyone appreciate your new UAS with this approach.

The truth is, there are certain things that we like having directly over our heads. Like mistletoe. Or baseball caps that hold two beers at a time with an elaborate system of straws so fans aren't troubled with the laborious task of lifting an Old Milwaukee to their mouths when the eighth inning drags on too long.

Of course, there are many other things that we don't like hovering over our heads. Like the 8 remaining EZ payments before I finally own that Bowflex I started buying in 1997. Or drones. Our aversion to drones directly above us might be fueled by self-preservation. Maybe they sound too much like insects. The mosquito, after all, has the distinction of being the only animal that kills more humans than, well, humans. Or maybe we just don't trust that the drone's battery won't give out while it's directly above our noggins, hovering in the “concussion landing zone.” It's also difficult to see in that position. Anything we can hear, we want to see. Our Spidey senses just need to know when something is up there and what it's doing.

The FAA doesn't make the prohibition against flying a drone directly over the heads of individuals difficult or nuanced.

Small unmanned aircraft may not operate over any personsnot directly participating in the operation, not under acovered structure, and not inside a covered stationaryvehicle

Summary of Small Unmanned Aircraft Rule (Part 107)

Again, even in this prohibition the exceptions are reasonable. These regulations understand that a drone pilot can't know he or she is flying over the head of someone who is under a roof or in a parked car. And the rules seem to suggest “Listen, buddy, if you want to fly your drone over your own head, knock yourself out.” Well, let's hope not literally.

Some have criticized the FAA for coming to the drone party too late. But its rules strike me as reasonable. They strike a balance between safety and the demand of recreational and commercial drone users.

Fly Close to Moving Cars

Everyone loves to drive a car down the highway like he's James Bond. What's a better way to spice up your driving than seeing that someone admires your sweet ride or your skills behind the wheel so much that he's following you with a drone. Who wouldn't want their driving to be considered “drone worthy”?

Cars make great photography subjects. The colors, shapes, and leading lines often make for fun compositions. Earlier this year, I went to the 2018 North American Auto Show in Detroit to get some images of some fantastic automobiles, both new models and some great classics. While it was very crowded and drones were not permitted in the convention center, the cars were also–and this is important–not moving!

Other distractions are also heavily regulated for drivers. When you drive down the highway in the South or Midwest and see one of the numerous–and I do mean numerous–billboards for Cracker Barrel restaurant, that billboard had to undergo a process of application–typically the state's Department or Bureau of Transportation–to determine if adding another billboard at that particular location was too distracting for drivers. Likewise, smartphones are engineered with options to discourage too much distraction and it's illegal to text and drive in most locations. These regulations haven't caught up yet to account for drones. Some day, there might be a way to measure and limit the acceptable number of drones within view of highway drivers–but we aren't there yet.

Fly over private property without the owner's permission

Airplanes fly over our heads every day. Why would somebody get all worked-up about a drone flying over her property? You can't own air, so go for it! They might even appreciate that you're keeping an eye on the neighborhood.

This is a recipe for bad photographer-neighbor relations. Like Middle East-neighbor-relations bad. Its also makes some assumptions about the law that are either simply untrue, or wildly oversimplify the state of residential airspace navigation.

As to whether a private property owner can bring a private lawsuit for a drone being over his or her property, that seems to be an unsettled issue. Traditionally, in the United States at least, the FAA has sole authority to regulate airspace. In December of 2015 the FAA released a fact sheet to clarify its supremacy in air regulation. However, the FAA regulation neither provides–nor prohibits–a basis for private lawsuits based on a traditional common law concept such as invasion of privacy. Many observers thought that the so-called “Drone Slayer” case working its way through a federal court in Kentucky would shed light on this question. Unfortunately (at least for those in search of clarity) the case was dismissed recently on jurisdictional grounds, and not decided in a way that creates a precedent for other courts to follow.

Since the FAA's 2015 statement suggests that trespass is a matter left to the States, it's at least conceivable that your neighbor's unwelcoming response to a drone 15 feet over his annual ladder-ball tournament Memorial Day weekend could have a basis in law. This would depend heavily on the facts, your location, and your neighbor's response.

But there's a bigger question at issue. Even if you could legally hover 20 feet over your neighbor's house with a drone, should you? I think the golden rule will do more to protect the reputation of UAS photographers (not to mention your investment) than the fine points of legal arguments. So ask yourself this: “Would I want that over my house?” The answer might differ depending on how high the drone is, how fast it's moving, whether the camera is active, and who resides there.

Ignore the “line of sight” rule

As long as you have a camera, you can see where you drone is and where it's going. There's no need to walk around and stare into the sky when you can use your smartphone to determine your drone's location. Besides, with all the collision-avoidance software built into drones today, you'd really have to be a loser to wreck a drone.

Sorry, bud. Rules are rules. And one of the basic and well-publicized rules for recreational drone pilots is to maintain the “line of sight” with the drone. It's not really ambiguous.

While it's true that drone cameras, flight reliability and crash-avoidance systems have greatly improved, there are some practical reasons to follow a ‘line of sight' rule beyond simply complying with the law. First there's quite a bit your drone's camera can't see. The Mavic Pro claims a 35mm format-equivalent 26mm lens, a field of view of 78.8°. And even if you did mount a 360° camera on a drone, how useful could it be? It's a novelty, but visually overwhelming.

Act like an entitled child when bystanders or the police ask about your drone flights

When some loser approaches you and challenges your God-given right to fly a drone, you have a responsibility to put that confrontation on YouTube and become a martyr for drone photography rights. You are the Rosa Parks of aerial imagery! You have a responsibility to all those coming after you to root out this ignorance in the loudest, snarkiest, most disrespectful way possible. Bonus points if you can get a cop involved and make the local news. That's how you change minds, bruh.

Whether you think that drones are the next big thing in photography, or a fad that future generations will only read about in a “Who remembers this random stuff from the 2010's?” Facebook clickbait ads, please be courteous. People will ask you questions. People may challenge why you're flying a drone, whether you're taking pictures or video, and whether you have a right to do so.

When this happens, please do your fellow photographers a favor. Don't be a schmuck.

Yes, you should know the FAA regulations and follow them carefully. But a little courtesy goes a long way. YouTube is replete with angry drone pilots facing off against angry neighbors or bystanders, and occasionally even law enforcement. I'm resisting the temptation to link to some of these. Mostly because I don't want to encourage the drama.

Conclusion

Truthfully, I've found hostility to drone photography to be the exception. Most people are simply curious. If you encounter someone who assumes that all drones are, ipso facto, an invasion of privacy no matter the circumstances, or comes to you with some level of ignorance, apprehension or fear, consider your opportunity. You're going to be the one who shapes their view of drones and photographers for years to come. Photographers, of all people, should understand the value of a moment in time.

Fly directly over the heads of people.

Fly directly over the heads of people.

The only time I’ve been asked about my drone flights was when I’ve been hired to photograph a house for a real estate listing. In these cases, the neighbors just want to know what some stranger is doing with a drone in their neighborhood. A simple “Mary hired me to photograph her house” has always enough to satisfy their curiosity. Sometimes I have the chance to show off the drone to a curious 5 year old with his mom nearby. Always fun to blow their minds by sending it soaring into the sky.

That’s the right way to do it, Kirk. Plus, it’s free marketing for more bookings!