Everybody knows that you can learn from looking at the work of great photographers. The question is: how? Do you simply absorb knowledge by being in the same room with a bunch of Ansel Adams prints? Or do you have to be more purposeful about it?

I wondered about that as I visited an exhibition with my wife recently. It was a showing of the best images from the 2018 World Press Photo Contest, organized by the Lightscape Foundation, here in Washington, DC, but it could just as easily have been any exhibit anywhere and any type of art. What could I learn from the artworks that would make my own photography better? What could I do that would make me more cognizant and appreciative of the artistry in the winning pieces? We came up with six tasks that I could set for myself as I went through the hallways. I think they might help anyone make their visit to an art space a very productive piece of learning.

It really doesn’t matter what kind of art you see. It could be photojournalism, as in the exhibit I saw. It could be a show of street photography, fashion shots, paintings, sculpture–any kind of art. It could even be that, the farther the type of art is removed from what you normally do, the better you are able to notice things and apply them to your own work, just because it’s so different.

There’s something quite distinctive about seeing an artwork in person, not on a screen or in a book. It might be bigger, bolder, sharper. It might reveal colors and details you don’t notice in reproductions. That’s especially true if the work is big. Some of the photos in the exhibit were several feet tall and wide. That made a difference. In Ryan Kelly’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of a car plowing into protesters against the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, the huge print reveals all kinds of details that are lost in smaller sizes. In addition to the horror or seeing people thrown up in the air, you see eyeglasses and a cell phone flying in space. Shoes and water bottles are airborne, the droplets of water spray frozen in time. You can read the signs and a bumper sticker on a parked truck, see the expressions on peoples’ faces. [I should note that photography was permitted, indeed encouraged, at this exhibit. These images were all shot with my phone.]

Art is everywhere

We’re lucky, here in DC, to have a variety of world-class museums, both publicly-funded and privately-run, as well as numerous galleries selling and displaying art. But you don’t have to live in New York or DC. Cities and towns of all sizes have art spaces. It might be a commercial gallery or it could be a room in a town hall. Maybe it’s at the school, library or church. The World Press Photo exhibit was in Dupont Underground, an old, underground streetcar station converted into an arts and event space. But, even if it’s simply looking at a coffee-table art book or seeing someone’s paintings hanging in the corner restaurant, you have a learning opportunity. Don’t waste it!

You probably already know where there are some pictures to view. Now, how do you know what you’re supposed to do to really get something out of the experience? A whole pile of education research points to the need to have some goals and outcomes in mind before going off on a field trip to the museum. So, let’s set ourselves some goals and make a list of things to investigate, observe, think about and enjoy.

1). Style

Examine two or three (or more) works by a single artist. How would you describe their style? Identify at least two elements that define that style.

You can often identify certain artists’ work without even seeing the caption, simply because you recognize their style. Ansel Adams typically had sharp focus from front to back, a rich and beautiful range of tones from pure black to white, for example. Whoever your favorite photographer is, they have a style you recognize and like. Recognizing, defining and analyzing the components that make up someone’s style can go a long way towards helping you develop your own signature style.

2). Technique

Find at least one technique that’s different from anything you’ve done before and, then, incorporate that technique into your photography. It might or might not work with your photos, but it could give you some ideas for variations on that technique. And, it stretches you creatively, which is always good. My mom was a painter and used to take a class from another artist solely because she always had them trying new things and that kept my mom’s painting fresh.

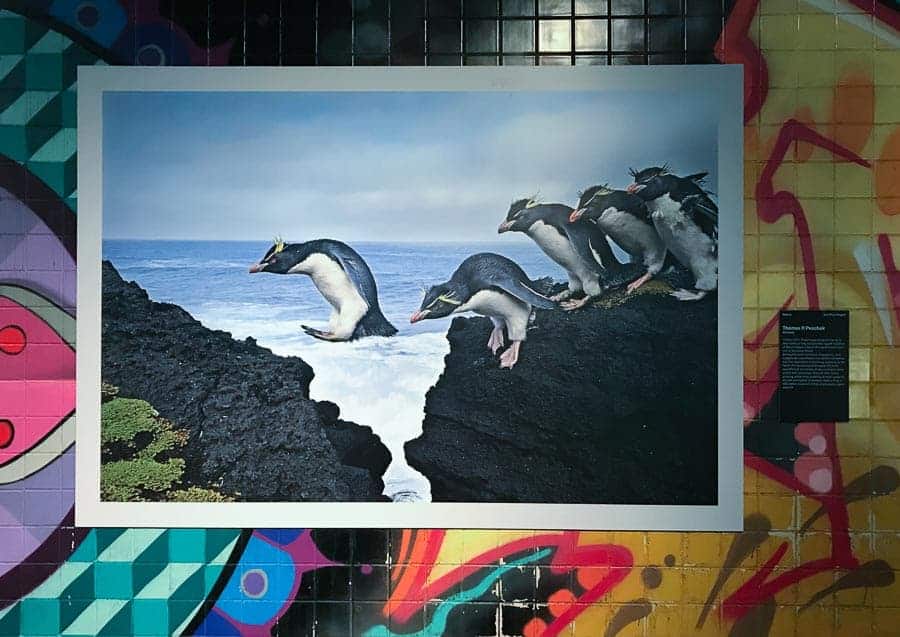

For example, Henri Cartier-Bresson was famous for capturing “the decisive moment” in street photography. Practicing how to identify and be ready for a decisive moment forces you to closely observe what’s going on and to anticipate what someone’s going to do. That’s pretty easy to apply to nature photography: being ready for the V of migrating geese to fly into your landscape in just the right spot, watching the osprey and knowing when it’s about to dive. Or Tomas Peschak being ready to snap the trigger at the exact moment a rock hopper penguin was completely in the air, with a line of others waiting impatiently behind it.

Maybe you’re looking at a cubist painting. How can you identify shapes in nature and compose those shapes into a work of modern art? The possibilities are endless.

3). First take, retake

Take a quick look at one photo that grabs your eye. What is your first reaction to it? What does it mean to you? Then read the caption. Does that information change your appreciation for and interactions with the art work? Come back after ten or fifteen minutes. Has your reaction changed?

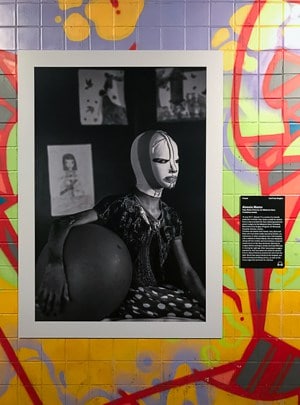

In the World Press Photo exhibition, there was a black and white photo by Alessio Mamo of a girl wearing a mask. She’s sitting in a room with some drawings on the wall behind her and has her arm around a large ball. Hmm, is she some kind of performer, wearing a mask? Is she from some tribe, wearing a traditional or symbolic mask that relates to her culture? There aren’t many clues in the photo.

When you read the caption, you find out that she was badly injured after an explosion in Iraq, with extensive burns to her face. She wears a mask to protect her skin from light, after having reconstructive plastic surgery. She was photographed in a hospital room in Jordan. Then you notice the burns on her arm. You have a very different feel for the photo and for the girl. How does a simple, descriptive caption change my perception of the photos? The meaning I make from them? The emotion they elicit from me?

Although a piece might stand on its own as a work of art, it is up to us to provide meaning and how we interpret it is a function of our own life experiences, beliefs and background. How, then, can a caption provide context and meaning that might be missing from an image? How do a few artfully-composed words change our perceptions and deepen or enrich our enjoyment? Do your images tell a complete story or do some need captions to be understood?

4). Fave

After you’ve seen the whole exhibit, pick your favorite piece. There’s usually one that stands out. It may be the one that you can’t get out of your head, or one that made you laugh, or cry, or cringe, or think. Why did you have such a strong reaction to that piece? What did the artist do that really grabbed you?

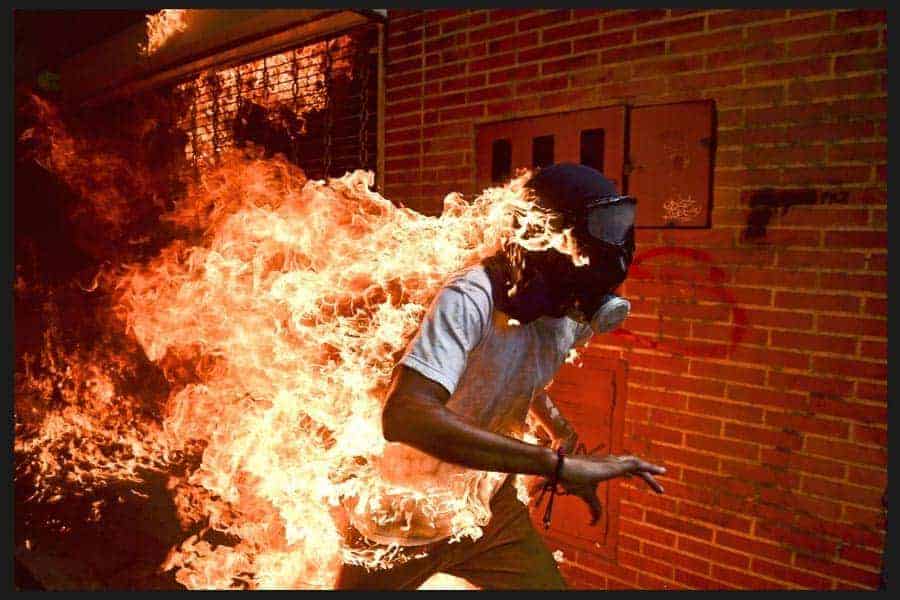

I’m going to be thinking for a long time. about Ronaldo Schemidt’s photo of a Venezuelan protester engulfed in flames I went back several times that evening for another look. Obviously, the subject is big, bold and attention grabbing. But also look at everything else about it. The action and urgency in the pose of the man. The way the flames streak out behind him and the thrust of his pose racing forward add a lot of energy and motion. The way the red-orange color carries throughout the frame, from flames to the brick wall to the metal fixtures on the wall. How red, as a color, signifies danger, passion and emotion and how that emphasizes what’s happening in the photo. With the hood and goggles, his face is obscured. He could be any protester, anywhere. A universal figure. And look at the wall to the right. There’s some graffiti—a gun and the word PAZ, Spanish for “peace.” An amazing shot, but you could do this with any work of art. Why do you like it? What did the artist do that makes it have such an impact?

5). Tell me a story

Discover a photo that tells a story you can relate to. How does the artist make a static object, like a photo, tell a story? Is it the composition? Lighting? An element in the picture? What is it that conveys emotions?

6). Dissect the photo

There’s a term, mise-en-scène (literally, “placed on the stage” or “staged”). It's used mostly in theater and movies and refers to the precise choice and placement of every element in the scene that's in front of the audience or camera. Mis-en-scène is often characterized by six elements:

- Composition: This is the most familiar to photographers. How do we organize the elements of a scene into a pleasing and coherent whole? We know the rule of thirds, use of real or implied shapes, and all the other “rules of composition.” How are those rules used? What makes the composition work?

- Costumes, poses and makeup: If there are people in the shot, their poses, costumes and makeup imply a lot about them and go a long way towards establishing a story. These elements are used as a sort of visual shorthand to give us cues about a character without having to explain everything. How are they used in the photo? What do they tell us about the people and the action?

- Set Design and Props: What does the set tell you? What are all the props? Why were they placed there? What function does each serve? In photography, ask yourself what function is played by each element, both large and small, in your photo. If something isn’t playing a meaningful role, why is it in there?

- Lighting: How does the intensity, color, direction and amount of light give the viewer cues? Think about how light was used in film noir, in the paintings of Vermeer or Rembrandt or in the great luminist paintings of Frederick Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt. Light can set emotional tones for an image, direct a viewer’s attention, reveal or conceal.

- Filmstock: Is this shot in black and white or color? Is it grainy or not? Are the colors muted or vivid? How does that choice affect a viewer? What messages does it send?

- Aspect Ratio: Are you always shooting images using your camera sensor’s aspect ratio? Maybe you crop later from 4 x 6 to 8 x 10 or square. Your choice of aspect ratio is an expressive one and shapes how that image is perceived. Maybe you should try composing with a specific aspect ratio in mind, rather than just using the one your camera gives you.

“Earth Kiln” is a gorgeous photo by Li Huaifeng of China. It depicts two brothers in a cave house in central China. The light streaming through the windows reminds you of a Vermeer painting (as does the dog!). This photo has a thousand things to notice, from the teapot on the windowsill to the DVD player the men are watching. Every little detail in this photo plays a role in telling a story. It’s worth spending some time with an image like this, savoring each facet of the setting for what it does for the whole.

Because these particular images are photojournalism, only the most minimal post processing is allowed and nothing can be staged. Many were shot by a photographer reacting in an instant. Yet these pros still show an amazing variety of personal styles, create incredible compositions on the fly, and really flex their technical and storytelling chops. Color me impressed!

So, there you have it. Six strategies to come home from an art display with some new knowledge, some techniques to try, and a better understanding of how other artists tell stories with their art. Well worth the price of admission in my book! And now I've got my work cut out, applying what I've learned to my own photography.

What are your favorite tips for a productive visit to a gallery or museum?

And, if you want to see all of the photos from the World Press Photo competition, look them up online at www.pressphoto.org.

How does a simple, descriptive caption change my perception of the photos?

Excellent. Thoughtful. Thank you.

Thanks for leaving your comments, Kevin. Appreciate the feedback and glad you found it useful.

I clearly remember that last time when I visited your site I was so impressed and this time very very impressed, thanks for the good content.

nice one…cant explain in my words this one was a beautifully written and a lengthy article as well which doesnt let you get bored at any point of time.

Thank You so much for sharing this article.

this one was a really nice article I know my words are not that good which will enable me to express how good you are but seriously this one was a good one. Thanks for sharing this.

Cheers Man

Absolutely Amazing , it has helped me significantly with my photography skills and creativeness aswell !!!

I clearly remember that last time when I visited your site I was so impressed and this time very very impressed, thanks for the good content.

good going guys this one was really amazing and opened my brain as a camera person.

Thanks for Sharing

Improve the photography with this is amazing.